The ACO’s Journal of Orgonomy is now on Substack featuring free articles from the Journal. Learn about Medical Orgone Therapy, Social Orgonomy, and Functional Thinking.

Medical Orgone Therapy*

Howard J Chavis, MD.

*This article is based on a lecture given at the New York Open Center, November 11, 1997.

Wilhelm Reich, a physician and a student and colleague of Sigmund Freud in the 1920s and early 1930s, developed medical orgone therapy, a unique therapy which addresses and dissolves chronic rigidities in both the patient's character and musculature. Orgone is the name Reich gave to the mass-free energy he discovered in his laboratory research in the middle part of the 1930s, in the atmosphere in 1940, and which he scientifically investigated1 until his death in 1957. Orgonomy is the science of orgone energy which includes medical orgonomy, orgone biology, orgone physics, sociology, meteorology, etc. In this discussion of medical orgone therapy I'm going to be talk ing about natural science which is the study or knowledge of objects and processes observable in nature. This includes all aspects of human functioning. I'm going to briefly describe how Reich came to develop medical orgone therapy and will include the major discoveries he made along the way. This will allow us to see the therapy and ourselves in a natural scientific perspective; that is, from the perspective of how nature functions.

1 Reich's work and that of others replicating his discoveries have been conducted according to rigorous scientific standards. The focus of this paper and limitation of space do not permit presentation and discussion of the experimental data and numerous observations supporting Reich's discovery of this mass-free energy found throughout nature. As an example, the Casimir force and the existence of a mass-free energy, predicted by quantum physics, has been confirmed by experimentation and reported in Physical Review Letters(1), Scientific American(2) and elsewhere.

First, I'd like you to look at the following brief videotape segment of a living amoeba seen through the microscope, magnified 800x. What do we see that is common to all of nature both in living and non-living systems? Spontaneous movement-expansion, contraction, pulsation. Now, if we think of expansion in terms of the weather, what constitutes expansion, an expansive day? And how do people feel on such a day? It's sunny and you feel positive, energetic, and outgoing. Conversely, what constitutes contraction, a contractive day? And how do you feel on such a day? It's cloudy, overcast, rainy, and people feel inwardly drawn, sometimes "low." Also, how do you feel and where do you feel it when you've just hit your best golf shot ever? Or you see your child take a first step? Or you reach out to hold your mate whom you haven't seen for an extended period? Conversely, how do you feel and where do you feel it when you realize that the car you're driving in has begun to slide on ice? Or when you're cruising along twelve miles per hour over the speed limit and suddenly see flashing red lights in your rear view mirror?

What I'm describing, by way of your own emotions, is that the human organism expands and contracts, it pulsates, and that this pulsation is a biological phenomenon. It is not a poetic metaphor. In a series of experiments Reich demonstrated that the subjective experience of pleasure and anxiety could be measured objectively. With the use of a vacuum tube amplifier and oscillograph he measured changes in potential at the skin surface. He found that stimuli that were perceived as pleasurable (such as sugar water on the tongue or a kiss by a subject's partner) elicited a positive deflection and that anxiety-provoking stimuli (such as a loud, unanticipated noise) elicited a deflection in the opposite direction. He also noted that the greater the intensity of pleasure or of anxiety felt, the greater the deflection mea sured. What Reich demonstrated he called "the basic antithesis of vegetative life"(3); that is, that pleasure and anxiety are opposite feelings. In other words, in pleasure something, which he later discovered to be orgone energy, moves out to the skin surface, toward the world and in anxiety something moves away from the skin, away from the world, toward the core of the body. Utilizing this observation, and the research of Kraus and Zondek, he discovered that pleasure is functionally identical to excitation of the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system and anxiety to excitation of the sympathetic branch. That is, when considered from the perspective of the total organism, excitation of parasympathetic and sympathetic innervations of bodily organs produces respectively expansion or "reaching out" and contraction or "withdrawal inward." With parasympathetic excitation, the internal organs actually contract forcing their contents toward the skin surface. With sympathetic excitation, the peripheral vasculature contracts and the internal organs relax or expand.

The meaning of this in terms of the vegetative antithesis is clear. The anatomic activities of the biosystem---contraction at the periphery and dilation in the core of the body-is consistent with movement away from the world.2 With parasympathetic excitation, or expansion, these functions are exactly opposite-there is a movement to ward the world. This is the mechanism that anchors pulsation in the body. We can also see biologic expansion and contraction described in figures of speech-chilling terror, bursting with enthusiasm, swollen with pride.

2 We can now understand from a functional perspective the distinction between the sympathetic branch's alpha and beta adrenergic receptors, a concept which arose from the observation that in some organs (e.g., the peripheral vasculature--alpha receptors) catecholamines trigger contraction of smooth muscle, while in others (e.g., bronchi, heart, splanchnic vascular bed-beta receptors) they induce relaxation.

Reich performed these experiments in 1934. In the six decades since, many of the intricacies of the autonomic nervous system and its two divisions have been explored and described by researchers and scientists. However, the concept of a biological periphery and core, and the significance of their excitation (toward the world in plea sure and away from the world in anxiety), has been overlooked by classical medicine and science. Just as we see spontaneous, biological movement in the expansion and contraction of the amoeba, a protozoan, there is a biological reality to expansion and contraction in the human organism, a metazoan with a developed nervous system.

How did Reich, a psychoanalyst, come to focus on excitation, expansion and contraction, on biological pulsation? We know from his own written description that he had always been interested in the "energy" process and that this for him received priority over "substance" or "matter"(4). As a medical student he was drawn to Freud and psychoanalysis because of Freud's psychic energy concept of libido and Freud's discovery of infantile and childhood sexuality-the psychosexual stages of development. Early in his analytic work, in fact only a couple of years after graduation from medical school, Reich made one of his most important clinical observations: when an inhibited patient, through treatment, was able to masturbate for the first time with pleasure his neurotic symptoms completely disappeared for a week, then reappeared, only to disappear again with pleasurable masturbation. Something fueled the neurotic symptoms and was discharged with pleasurable sexual release. This observation led to Reich's discovery of the pulsatory, bioenergetic function of sexuality3; of orgastic potency4-the capacity to allow energy to flow freely into the genital and to be completely discharged, without any inhibition, through involuntary, pleasurable contractions of the whole body musculature; and the function of the orgasm-to discharge energy as the ultimate regulator of the organism's energy economy.

3 In his investigation of the sexual function Reich discovered that physiologic (mechanical) swelling of tissues precedes bioenergetic charging; that increasing bioenergetic excitation culminates in spontaneous, bioenergetic discharge which is followed by physiologic (mechanical) relaxation. He described this schematically in the orgasm formula:

tension - charge - discharge - relaxation

When Reich recognized this sequence in physiologic processes in living organisms (including mitosis, peristalsis, urinary bladder function, etc.) he re-named the equation the "life formula"(5).

4 Classical medicine defines "sexual potency" in terms of mechanical function-the capacity to have an erection, to have vaginal lubrication, to ejaculate, etc. Reich noted that some individuals meet these criteria but feel little or no pleasure in the sexual embrace, or experience symptoms of incomplete bioenergetic discharge. He pointed out that these classically described mechanical factors are merely prerequisites for orgastic potency.

Early in his analytic work Reich's search for the emotional intensity so often absent in his patients led to his discovery that feelings were bound up in and by rigid character reactions and structure what he called "character armor." Not only was this contrary to the idea held by psychoanalysts that people with neurotic symptoms such as phobias, compulsions and irrational anxieties were otherwise healthy, it was also the first time that the character-the chronic characteristic way an individual interacts with the world-was identified as defensive. In other words, the individual's way of being and reacting protects against perceived dangers both from the outside world and from impulses and emotions within. He pointed out that in our neurotic world, character in general, and specific character types in particular, are formed in everyone according to certain determinants but always as the result of a traumatic conflict between the child's individual, spontaneous expressions-natural impulses-and the limitations imposed by the environment, usually the parents(6). Interestingly, this view of character as a traumatic wounding, as a"scarring" fits with the etymological origins of the word "character" from "kharesien" to mark or brand from the Inda-European "gher" which means mark or brand. Gash is the only other English word from this root(7). Although its original function is positive, protection, there is a cost to this scarring, this armor. There is a decrease in emotional motility and liveliness, a decrease in the ability to open oneself to a situation or to close up against it. However the individual's character is described, whatever its characteristic attitudes or character traits, all are merely different forms of the same thing-armoring against intolerable intensities of feeling. Exaggerated congeniality or politeness in one individual serves the same function as "macho" or harsh aggressivity in another. Remember: these attitudes, the characteristic way or ways each individual has in relating to others, is a protective mechanism. If we think in terms of our dear little amoeba, its membrane would no longer be fluid and free-flowing, but hardened. It's not difficult to imagine the consequences for our one-celled friend.

I want to emphasize again that the identity of the plasmatic functioning of the amoeba and the human organism is not a product of poetic creativity or a metaphor. In the late 1920s Reich observed that individuals with rigid character defenses (rigid character armor) also had muscular hypertrophy and rigidity. And that the greater the character rigidity, the greater the muscular rigidity. When the patient's character defenses yielded to character-analysis-the approach Reich developed to dissolve character armor-the chronic muscular rigidity also softened. Reich saw with one particular patient who had a "stiff-necked" attitude that when the defense finally let go the patient experienced dramatic autonomic discharge in the face and neck. Reich realized then that the chronic character attitude and the patient's chronic muscular rigidity were functionally identical-both contained and held back vegetative energies, sensations, and emotions. It was in this way that Reich came to discover muscular armor and its function, which led him to work directly on chronically tense musculature.

In its acute form armor is a natural biological defense. It is some times even seen in newborns. We all tense up in stressful situations and hold our breath, but we then relax and let go when the situation passes. When muscular armoring becomes chronic, however, it interferes with natural emotional and physical motility. Depending on the degree of its severity and distribution it can also interfere with natural physiologic processes.

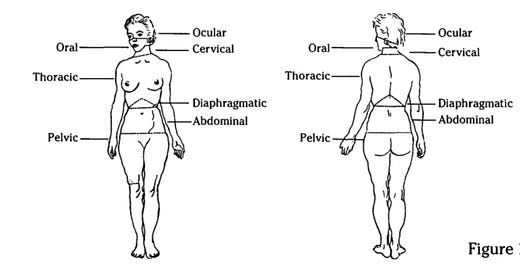

Reich described the anatomical distribution of human skeletal musculature as segments arranged perpendicular to the long axis of the body-much like the annular segments of a snake or worm. There are seven segments: ocular, oral, cervical, thoracic, diaphragmatic, abdominal, and pelvic(8).(See Figure 1)

Clinical experience reveals that muscular armoring is laid down in these segments in a functional distribution. For example, when the newborn reaches out with its eyes to the mother as part of the natural process of newborn-maternal bonding and it sees anxiety, cold ness or hatred, it will pull back and contract, especially in the ocular segment. If this is unrelieved by maternal warmth and contact then the armoring of the ocular segment-the eyes, the scalp, the occiput, and even the brain (if the trauma is severe enough) will persist. (Ocular armoring occurs at other times as well.) If the child is not al lowed to speak, it must hold back the impulse and does so with ten sion in the throat, mouth, neck and upper thorax. If breast-feeding is stopped prematurely or if it is accompanied by maternal anxiety or disgust, the infant may armor in the mouth, with tension in the masseters, the extra-oral musculature, and the back of the neck. Premature toilet training before the infant is developmentally ready, before there is neuromuscular control of the anal sphincter, can only succeed through contraction of the muscles of the pelvic floor, the buttocks and thighs aided by retraction of the pelvis and inhibition of respiration. And so muscular armor is laid down, layer upon layer, during the child's development and is the somatic basis of armored character formation and the armored character itself.5

5 While armoring during childhood development determines character, additional layers of armor may develop throughout the individual's life.

Muscular armoring can be identified and demonstrated clinically just as physicians learn to identify pathological physical phenomena in their medical school course in physical diagnosis. Examples are present before everyone: How expressive are the eyes? Can they show the full range of emotion? Are they dull? Is the face mobile and expressive? Is the jaw set? Is there spontaneous, full respiration? Is the chest held in an inspiratory position? Is the voice caught in the throat, like Henry Kissinger's? Does the abdomen balloon on expiration? There is much, much more visible to the discerning, trained observer. Because it blocks movement of sensation and emotion, armoring al ways interferes with the individual's ability to make contact with them selves, with others, and with the world. Contact, the quality you might say of "being there," the ability to make and sustain an emotional-energetic connection, is determined by the capacity to tolerate intensities of sensation. Although contact may be voluntarily withdrawn in sleep or during a boring lecture by "going off" in the eyes, with chronic armoring there is always some degree of contactlessness. Armoring and the resultant contactlessness are the biologic, biophysical bases of perceptual distortion.

For the medical orgonomist health is not simply the absence of disease. There is an objective standard of health. This can be demonstrated, in large measure, by having the individual lie supine on the couch. Without significant armoring, respiration is full, natural, and relaxed. Toward the end of expiration the head tilts spontaneously back, the shoulders move gently and slightly forward, and as the wave of respiration moves down the body the pelvis tilts slightly forward. Reich called this movement the orgasm reflex. For such an individual affect is natural, the eyes are expressive, aggression is without sadism, the work function is unimpaired, and the individual is capable of independence and responsibility. Although there may be armoring, this is after all a functional definition of health and not an idealized one, what armor there is does not substantially interfere with the individual's functioning in the different aspects of life. This includes the capacity to experience a full and gratifying orgasm with a mate of the opposite sex (orgastic potency).

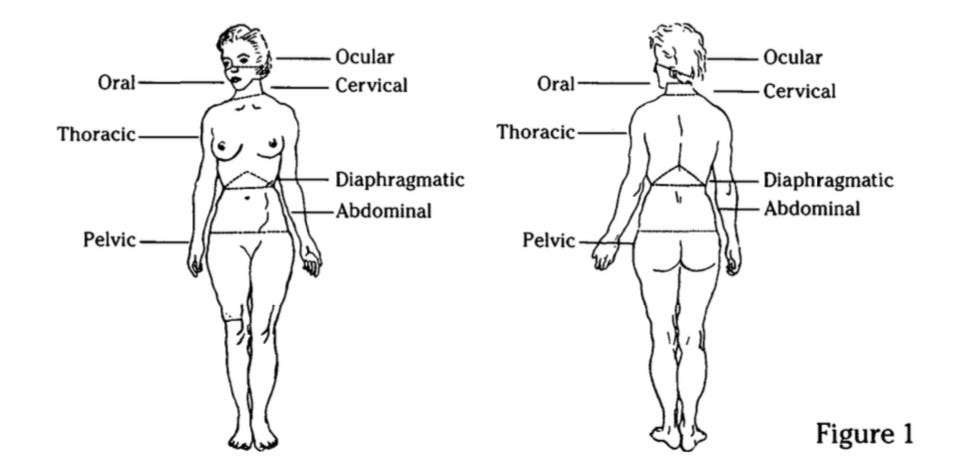

The structure of the individual without significant armoring is graphically portrayed in Figure 2 (after Reich)(9). It show the three layers of the unarmored human emotional structure.

Figure 2

The biological core is the home of our individual nature, what we're born with, the source of our healthy, primary impulses. The social layer is that part of our structure which interfaces with the world. In health, this layer is in more or less direct contact with the biological core. The middle layer contains the armor which, in health, is transitory-we defend and hold back feelings when necessary but then let go. When armor becomes chronic, however, the social aspect becomes a social veneer or facade which is separated from the core by the secondary or great middle layer (see Figure 3)(10).

This is the repository of the harsh, destructive secondary impulses which form as the result of the frustration and distortion of core impulses as they try to break through the armor. Chronic armoring is the source of human destructiveness. The social facade then has a defensive function-its sociability and rules protect against expression of these destructive impulses.

From Figures 2 and 3 we can clearly see the logical goal of therapy. It is to remove the restrictions to the free flow of energy throughout the body, to restore the individual's capacity for natural bioemotional, bioenergetic pulsation. In practical terms the goal is to dissolve chronic characterologic and muscular armor and restore the individual's capacity for making and sustaining emotional contact. In other words, to restore our capacity to be spontaneous and free-flowing, like the amoeba, when external circumstances allow.

There are three basic tools the medical orgonomist uses in this task. One is to have the patient breathe fully, but not in a forced or mechanical fashion. This builds up or excites the individual's energy charge which, in turn, exerts a push against the armor. Some holding then often yields with the spontaneous release of crying, anger, fear or other emotions. A patient came to me saying, "I need to cry, but I can't." She felt frustrated, anxious and blocked. Her previous "talk therapy" had been unable to help her. On biophysical examination I saw that she had significant holding in her chest, which appeared immobile, and some holding in her face. On the couch I had her breathe and move her face. After a few minutes she began to cry, first without sound, then with sobbing from deep within her chest. This continued for about fifteen minutes. She reported feeling deeply sad while cry ing but she did not know why. She also said she felt relieved.

Another tool employed by the medical orgonomist is direct work on the patient's spastic, tense musculature. The general principle is simple-pressing on a tense muscle causes it to contract; continued pressure causes continued contraction and ultimately fatigue of that muscle. It "lets go" and whatever emotion was held back by the tense muscle is released. If there is a discrete experience, such as a specific traumatic event, associated with that held-back emotion, the individual will often relive the experience complete with the long-repressed emotion. There is a feeling of great relief with this emotional release. A patient with hypertension was referred by his cardiologist because of depression. Biophysically, he was armored throughout but especially in his chest which was held high in an inspiratory attitude.6 Over several sessions, with the patient on the couch, I was able to bring his chest down by pressing on it with gradually increasing pressure. I encouraged him to let out any sounds and to move his face. At first in distinct, his sounds and facial expression began to reveal fear. This was gradually replaced by angry growling and yelling. With increased pressure on his chest, he was soon expressing intense rage which lasted about fifteen minutes. Afterwards, he told me how eight years before he was on a city bus and witnessed some young toughs taunt an elderly woman and steal her pocket book. No one said or did anything. He alone told them to give the woman back her bag. One of the gang came toward my patient in a threatening way, reaching into a paper bag he was carrying. My patient was terrified and was convinced he'd have to fight for his life. Just then the police arrived and arrested the toughs. There was a gun in the paper bag. Clearly, my patient had spontaneously expressed the intense emotion he experienced eight years be fore, but which had not been released and instead held in his chest.

6 This configuration of the chest is commonly seen in those individuals with cardio vascular disease.

In general, the work on the musculature proceeds from the upper segments-ocular, oral etc.-down to the pelvis which, except in rare instances, is always freed last. This allows for removal of holding in the upper segments first which ensures that earlier problems, such as sadistic impulses or hate held in the mouth or the chest, are resolved. Freeing the seven segments in their order also helps reveal or bring to the fore deeper holding that needs to be addressed. Any one segment, however, may fail to respond completely until further segments are freed. With each release of a segment, armoring in earlier segments may recur and require further attention-the organism is not used to movement and tries to return to its former state of immobility. The individual must be gradually accustomed to free motility. This requires that the therapist not only have thorough training but also, and especially, sufficient health. In practical terms: the therapist must be able to tolerate the intensities of emotion experienced and released by the patient. The therapist's own treatment is thus the cornerstone of the training program of the American College of Orgonomy.

The third tool of the medical orgonomist is character-analysis, wherein the patient's defensive attitudes and behaviors are addressed. Consistently pointing these out to the patient dissolves ocular armoring because it obliges the patient to "see" that and how he or she is defending. It focuses attention on how the individual communicates-his or her look, manner of speech, dress, facial expression, language-not simply on what is being said. This brings the patient into better contact with him or herself and can also unmask disguised or hidden negative attitudes toward the therapist and the treatment. These can then be expressed and dissolved. It is important to maintain cooperation because patients will always try to sustain their armored state. I began to notice that one patient ended many of his sentences with a slight raised inflection of his voice. I drew his attention to this and he said he was unaware of this change in his tone of voice. I continued to report this observation to him. After the fifth or sixth time he realized he was speaking in this way because he was try ing to elicit a response from me. In actuality, he thought I was cold and distant and was angry with me. Another patient was lying on the couch and I observed how composed she looked and also that she was hold ing onto a balled-up tissue. (She wasn't clutching it which would have been obvious.) When I pointed out to her that she was holding a tis sue she immediately said, "I'm holding on, I'm so scared," and she started crying and shaking all over. Another patient who had been in treatment with many different therapists over the course of years sat in a relaxed, casual way during his first session. While he was re counting his history I asked him, "Do you feel as relaxed as you look?" He looked surprised, said "No" and then after a pause told me how he always tried to portray himself as relaxed. He felt it "disarmed" the person he was sitting with which allowed him to control his anxiety. No one had ever asked him about his relaxed manner. Another patient shuffled her feet walking into my office. I pointed this out to her by shuffling my own feet. At first she laughed but then started to cry. She felt victimized by the world. When we looked into this attitude, which was quite familiar to her, she saw how passive she was and how scared she was of sticking up for herself.

In sum, the medical orgonomist uses all three avenues of approach with every patient, the importance of each depends on the individual patient and the particular circumstances at the moment. The idea that medical orgone therapy is just "body work" or only employs physical technique is an unfortunate, common misunderstanding. A patient came to me wanting "body work" so he could "get to the depths." Although he was on the couch, I declined to work biophysically. Slowly but surely his characterological sneakiness and hidden nastiness came to the fore in therapy, as did accounts of the dysfunctional way he lived his life and related to others. All this would have been easily missed if I had ignored his character armor and acceded to his wishes for "body work."

In closing, I want to point out, in a cautionary way, that having an emotional release or "moving energy" does not constitute medical or gone therapy. These experiences may excite people who are looking to feel more but in and of themselves they can only bring superficial and often temporary relief. There is no substitute for a functional, bioenergetic understanding of the patient's defensive structure, which includes both muscular and characterologic armor. Medical orgone therapy increases individuals' capacity for satisfaction in life, love, and work. It does so by effectively addressing the biological basis of their emotional and psychological difficulties-the disturbance of natural functioning by chronic armoring.

REFERENCES

1. Lamoreaux, S. "Demonstration of the Casimir Force in the 0.6 to

6µm Range," Physical Review Letters, 78(1): 5-8, 1997.

2. Yam, P. "Exploiting Zero Point Energy," Scientific American,

December 1997.

3. Reich, W. "The Basic Antithesis of Vegetative Life," The Function of the Orgasm. New York: Orgone Institute Press, 1942,

pp. 255-265.

4. Reich, W. "Orgonomic Functionalism. Part II On the Historical Development of Orgonomic Functionalism," Orgone Energy Bulletin, New York: Orgone Institute Press, 2(1): 1-4, 1950.

5. Reich, W. "The Orgasm Formula," The Function of the Orgasm.

New York: Orgone Institute Press, 1942, pp. 243-255.

6. Reich, W. Character Analysis. New York: Orgone Institute Press, 1949.

7. Crist, P. "Nature, Character, and Personality," Journal of Orgonomy, 27(1):51, 1993.

8. Baker, E. Man In The Trap. New York: Macmillan, 1967,

pp. 42-43.

9. Reich, W. The Function of the Orgasm. 261.

10. Ibid, 262.